My main gig as a university professor has given me the opportunity to cultivate an immense website of my translations from Old English. This archive collects my first efforts translating what’s left of its poetry. Though it’s not entirely complete, even since 2007 — the project now includes some 29,000 lines. Only some very minor poems are still missing, mostly things not collected in the big ASPR edition.1 Most of it is older, when I still was learning Old English, and so errors & misunderstandings abound. I was still bound to current glossaries & published, more canonical translations.

But the intervening years have given me many occasions to re-consider the standard readings of many classic moments in the verse & to think beyond commonplace ideas about its culture. My goal was always to provide current, fresh, & interesting versions of these texts from across the Old English corpus, and to keep them open-access for a broad range of teachers & enthusiasts to use & enjoy.

This is all offered on a Wordpress site, & because of this, anyone who reads can respond. I moderate these comments, because most are spam. Occasionally I get questions that allow me to redress a likely error or clarify a reading. At times, people want to know why I believe this thing or that about the texts, or the culture, or the tradition — and at times these questions are civil & curious enough to merit detailed response. Some are hostile, abusive, or just plain weird. Most are repetitive & dull, raising points raised over & over again (& usually always explained downthread).

However, many of these queries, especially the more hostile, originate in very common misprisions regarding the art & craft of translation. To most, the idea that there is either an art or a craft to it is tough to believe. A whole field of translation theory has developed over the centuries to accommodate the intricacies & delicacies of the process.

This feature, “Translating in the Trenches,” which may prove semi-regular, attempts to unravel some of these misgivings by introducing the theory that questions their origins. The first part begins beneath the “Subscribe” button.

So for the legal part:

My comments here or on The Old English Poetry Project do not reflect the views of Rutgers University. They are based in my researching & teaching Old English, studying translation theory, & my experience translating this body of literature. My goal here is to maintain a degree of civility to those who come in the spirit of good faith inquiry. But I do not feel any need to abide those who are rude, abusive, time-wasting, or cannot provide any evidence for their claims.

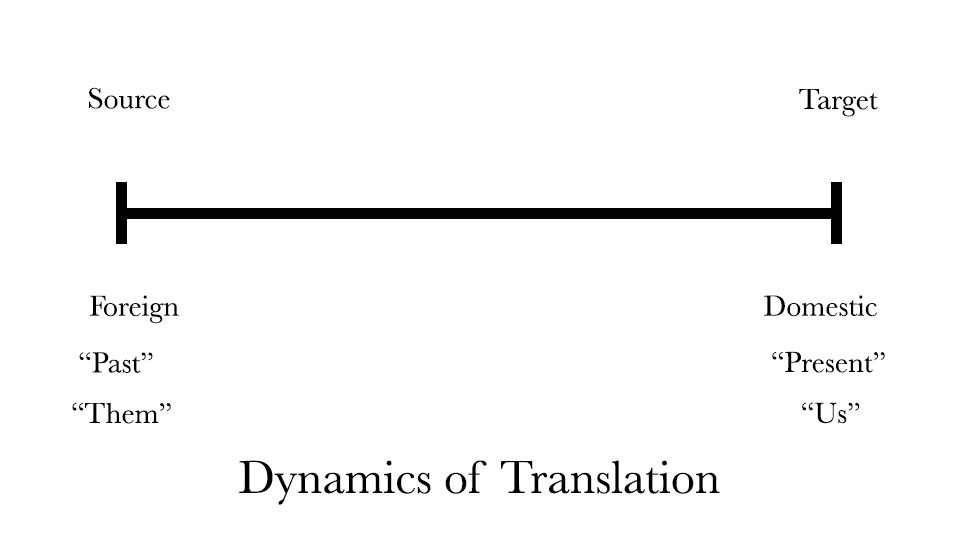

Fig. 1: Betraying the Tradition —

By far the most common criticism I receive about my posted translations involves a disagreement about whether some word is “right” or “proper” for the text itself. This is to be expected — a carefully-thought-out & well-wrought translation is a tapestry of hundreds if not thousands of decisions. Some of those choices are bound to elicit disagreement. How could they not?

Yet these differ in an important way: these critiques are not about the poem itself. Rather, these commenters are absolutely sure that some choice of mine “betrays” the presumably noble, virtuous, & often pious spirit of the early English. If these poems don’t sound like Wagnerian opera characters or the King James Bible, then we may as well shit on the tomb of King Alfred himself (he was Great, you know…).2 To these readers, my rendering offends the vibe of Old English poetry that they were taught in high school or university literature classes. These are old-fashioned assumptions, but they are still widely held & commonly taught, and these attitudes concatenate from every corner of the field. But they are only assumptions.

Let me repeat: THEY ARE ONLY ASSUMPTIONS.

This brings me to the Matter At Hand — the aspect of Translation Theory I wish to introduce as a challenge to those who feel the need to defend the integrity of “Anglo-Saxon culture” against my efforts to translate its works in a new voice, seeking to discover new ways of understanding this era of history.

Theorem #1: Translation Is Only Done to Address Our Needs

Translation theorist Lawrence Venuti relates a reviewer’s response to his translations of works by 19th-century Tuscan novelist I. U. Tarchetti (1839–69). Venuti describes Tarchetti as a bohemian, who sought to shock Italian bourgeois sensibilities by experimenting with Gothic fiction and by thwarting the linguistic conventions of the Italian literary tradition. Venuti characterizes these deliberate stylistic quirks as a way to “minoritize” the canons of taste Tarchetti struggled to challenge & exceed. Based in an idea from the philosophers Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari, a “minoritizing project” of translation resists the hegemonic pressure of a received standard dialect of any language.3 With this program in mind, Venuti advocated for an approach to translating Tarchetti that exposes the text’s heterogeneity, celebrating the ways that this novel & its writer were unlike any other.

Many of these translations were were well-received.4 However, a reviewer for the New York Times found fault with Venuti’s efforts, not only because the translation disappointed their expectation for “melodramatic romance,” but also their “investment in an ethnic stereotype, the equation of ‘Italian’ with intense emotion.”5 This critic assumed any literary experience that sounded any other way must be a failure. Perhaps the translator wasn’t skilled enough or knowledgeable in the language? Perhaps they were “interfering in the process” by interpreting the text? By failing to deliver exactly what the reviewer was already expecting from the translation of a 19th-century Italian novel, rendered in an unobtrusive, transparent manner, Venuti had apparently created a bad example of translation.

But had he really?

In seeking to convey the heterogeneity of Tarchetti’s writing, Venuti had exposed how translation functions to shape domestic identities through caricatures of foreign identities, a process that works through complacency & repetition to give a flattened, oversimplified image of other cultures. These gain the status of what’s “natural” or “real.” He writes:

Translation wields enormous power in constructing representations of foreign cultures. The selection of foreign texts and the development of translation strategies can establish peculiarly domestic canons for foreign literatures, canons that conform to domestic aesthetic values and therefore reveal exclusions and admissions, centers and peripheries that deviate from those current in the foreign language.6

Because most people do not have a direct experience of a foreign culture, they must rely on translations for what information they desire. However, because translations are produced from within the domestic culture (or at least, for its benefit), these perspectives are reduced to accord with what the domestic culture already thinks it knows about them.

Venuti continues: “Translation patterns that come to be fairly established fix stereotypes for foreign cultures, excluding values, debates, and conflicts that don’t appear to serve domestic agendas.”7 Not only are these texts separated from their historical, political, & social contexts, but any of those aspects that do not suit the needs of the translating culture are ignored or misunderstood. The voice of the text itself is supplanted by either a bland “translator-speak,” pretending at objectivity, or else presented in the style & tone the domestic culture currently associates with the source culture & its texts.

Venuti’s concept of “heterogeneity” is an ample defense against the comments on my translation site complaining about whether my work “sounds right” for these Old English poems. What sounds right to these readers is overwhelmingly based on an ethnic stereotype of early English culture. And like most stereotypes it was created by someone else — in this case, an academic tradition fraught with an nefarious agenda as well as melancholia, neurosis, & nostalgia.8 At the very least, most lay-folk who admire this era’s literature do so because they feel the era embodies some attribute they feel the modern world has lost. Most often, that is expressed as a respect for tradition, some degree of cultural seriousness, maybe piety or religiosity.

Yet, as I indicated above, these assumptions are based on drastic oversimplifications & generalizations, & arising from the colonizing, imperialist origins of the field. The common stereotype of the early English as pious is derived from the literature, but this is a literature produced solely by the monastic class & almost entirely for the benefit of those same monks. It never represented the whole of society nor was ever meant to. Also, there is zero evidence showing that warriors or aristocrats, the types of people usually represented in the corpus, were directly consuming these works.

Further, these ideas are based in a myth of early Germanic culture, that because they were primitive —“noble savages,” as it were— they were incapable of lying.9 Therefore, whatever these people represented of themselves must be the Whole Truth. By this logic, historical chronicles, charters, and royal genealogies had to be unimpeachable in their facts — and of course, there is no such thing as propaganda.

Also, attitudes as this usually hold that early English writers avoided any serious form of irony — at least, not where it might challenge either of the values mentioned above. Literary effects we take for granted —irony, dark implication, sarcasm, satire, political or social critique— all of these are presumed foreign to the “pure & primal” spirit of Old English poetry. Sometimes the appearance of these devices is attributed to the interference of Other Cultures: Scandinavian, Celtic, or <shudder!> French — or else the unfortunate withering effects of Modernity on some mythical ideal of Western European culture. These cultural narratives I reject wholesale.

However, to see the medieval world as uncomplicated, black-&-white, or socially placcid is a useless fantasy. Youth strained against previous generations, mortifying their elders with their changes to language & mores. Peasants & laborers resisted their oppression by aristocrats & other landowners. Trade & diplomacy brought people great distances into contact with Europeans, yet Europe was a relative backwater in terms of technology & cultural sophistication. Women defied a different set of gender expectations. Queer people existed, even if the labels we use were unknown. Atheists existed, even in monasteries.

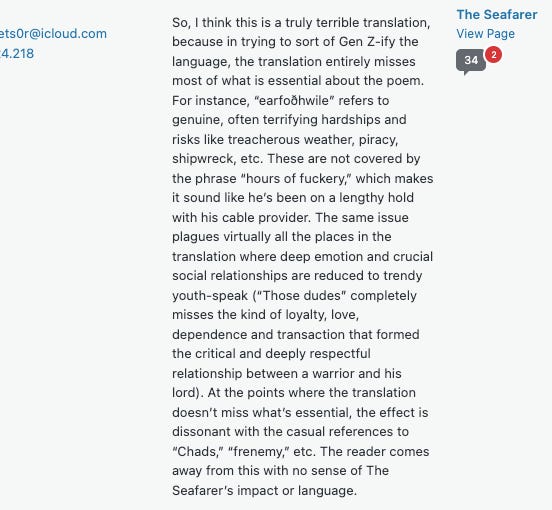

In the case of the comment embedded above, its writer decries how my word-choice does not adequately reflect their cherished view of how early English people spoke or thought. In particular, they are displeased with “those dudes” (which appears in my (re)translation of “The Seafarer,” for ll. 80b–85 - it renders “hī” [those ones, they]), saying the phrase “completely misses the kind of loyalty, love, dependence and transaction that formed the critical and deeply respectful relationship between a warrior and his lord.” I guess my response is that this sounds like a person who has never had “dudes” or “bros.” Or who assumes modern male friendships & alliances are not somehow comparable to their distant counterparts.

When I seek to unlock the heterogeneous in my work, it is because I see possibilities for not only complication, challenging these oldy-moldy assumptions & oversimplifications of tone & audience, but also for seeking what Chris Jones might term “strange likeness”: that even across a millennium, there may be aspects of human life & human society that may find some equivalence. The way I see it, (re)translation is one response to the challenge extended by Delphine Grass in her recent study of translation, promoting “creative-critical translation practice as a way of interrogating the histories and ideologies embedded in the traditional separation between theory and practice in translation studies.”10 Like Grass argues, by melding these two modes of textual engagement, I can dwell closer to a text than traditional approaches have allowed and, by sitting with that discomfort & estrangement, start asking more challenging questions about these poems & the scholarly tradition that has fixed their form & voice for many decades.

I’ll end these notes with further insight from Lawrence Venuti:

A translation ethics, clearly, can’t be restricted to a notion of fidelity. Not only does a translation constitute an interpretation of the foreign text, varying with different cultural situation at different historical moments, but canons of accuracy are articulated and applied in the domestic culture and therefore are basically ethnocentric, no matter how seemingly faithful, no matter how linguistically correct.11

If we only translate for our own purposes, to suit our own preconceived notions of foreign cultures & distant times, then the idea of “fidelity” is specious, distracting. It can only be used to discourage critique of the interpretations & ideological demands already baked into reception of a translated text. Its implicit charge that is the translator doesn’t know enough about the language or its culture to question anything — and therefore nothing changes. And in many ways early English studies has changed very little since the days of Kemp Malone & Frederick Klaeber. But maybe it could if interesting & theoretically-aware scholars, particularly scholars of various identity would come on over to play. So far the ubiquity of boring translations has worked according to plan — to only draw the fancy of the boring or the resentful. Venuti again brings the goods: “In attempting to straddle the foreign and domestic cultures as well as domestic readerships, a translation practice cannot fail to produce a text that is a potential source of cultural change.”12 This is why translation is so zealously policed & controlled: because it has always contained revolutionary potential. Heterogeneity is the best way to challenge orthodoxy. The stakes, as is plain to see with my aforementioned friend the anonymous commenter, are not just “bad translation” but becoming traitor to a tradition & its demands.

Yet there are & always will be many styles of translation, all with different goals & purposes. It is a major default of our language that we have never developed a better range of terminology for these different kinds of translation. There are also dozens of translations of the major Old English poems (& for Beowulf, hundreds) — most nice & placid & quiet & meek. These ones will always give a reader what they expect & never challenge a thing. But I didn’t begin this project of “(Re)translation” to be quiet & meek — or to sound exactly like everyone else. My goal is to use translation to create new knowledge about these poems, using the language that’s already there, considered in new ways. In no way are they meant to replace existing translations. There can be many translations of any text you like — and translations come & go in & out of style.

If you don’t like mine, go find one you like — or better yet, go write your own.

Please check out my translation page “The Old English Poetry Project”

The Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records, in 6 volumes, edited by George Krapp & Elliott Van Kirk Dobbie (Columbia University Press, 1931–42). Most scholars still rely on these editions for their texts, even though better & more authoritative versions have been produced since. The total number is somewhat fuzzy, perhaps no more than 34,000 lines.

Erik Wade explores the implications of a spirited, though absolutely specious, scholarly debate among historians in the early 1990s, to defend King Alfred the Great from not only imputations of homosexuality, but also, what’s worse, being a bottom. (“Skeletons in the Closet

Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Une mille plateaux, 1980), translated by Brian Massumi (University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 105ff.

Venuti’s translation of Tarchetti’s Fosca in part inspired the 1994 Tony Award-winning musical Passion by Stephen Sondheim & James Lapine. So pretty good reception, I’d think.

Lawrence Venuti, The Scandals of Translation: Towards an Ethics of Difference (Routledge, 1998), 19.

Venuti, Scandals of Translation, 67.

Venuti, Scandals of Translation, 67.

For the melancholia of early English studies, see Donna Beth Ellard, Anglo-Saxon(ist) Pasts, Post-Saxon Futures (punctum, 2021).

Much of the evidence for “primal purity” of the Germanic tribes is derived from the Roman historian Tacitus (ca. 56– ca. 120 CE) and his tract, the Germania (ca. 98 CE). However, Tacitus’s information was never based in firsthand observation & many scholars suspect the tract was composed as a sort of social satire, or implicit castigation of contemporary Roman mores. See M. J. Toswell, “Tacitus, Old English Heroic Poetry, and Ethnographic Preconceptions,” in Studies in English Language & Literature: “Doubt Wisely,” Papers in Honour of E. G. Stanley, edited by M. J. Toswell & E. M. Tyler (Routledge, 1996) and numerous chapters in The Cambridge Companion to Tacitus, edited by A. J. Woodman (Cambridge University Press, 2009), esp. ch. 5 by Richard F. Thomas, ch. 12 by Miriam T. Griffith, & ch. 15 by Christopher B. Krebs. Also valuable is Krebs’ full study, A Most Dangerous Book: Tacitus’ “Germania” from the Roman Empire to the Third Reich (Norton, 2011).

Delphine Grass, Translation as a Critical-Creative Practice (Cambridge University Press, 2023), 4.

Venuti, Scandals of Translation, 81

Venuti, Scandals of Translation, 87.

Translation is often a hard and thankless job (not to mention underappreciated) — keep up the amazing work.