Uncrossing Exeter Book Riddle 53

Playing & Puzzling at the Unsolvable

I offer a sheepish apology for my scarcity in posting recently. Classes have started & I’ve been wrapped up in handling revision deadlines on a few forthcoming articles. Conveniently however, I’ve stumbled across something worth chatting about to y’all. And it goes a little something like this…

The Queer Life of Riddles, my collection of creative-critical translations of the Exeter Book Riddles, is working its way through the publication process. Taking its time of course, but that unexpected time brings an opportunity to revisit the individual riddles & see how I still like them. Many have been sitting in their present form for several years. Others were churned out in that last rush to the deadline. So I thought it might be a Cunning Plan to decide what I have learned about some of these since May 2024. After all, my process of “Queer/Translation” has not exactly been sitting around waiting for someone to ask her to dance…

Exeter Book Riddle 53 (ASPR #55) is a strange riddle — but I had never really thought about how strange it is. For some reason I had locked on the solution of “Cross” but have recently realized there’s no consensus for a solution at all. This in itself is not unusual: about six or seven Riddles in the collection (that are mostly complete) do not have an agreed-upon solution.1

Bernard Muir states the solution is “Uncertain, but some sort of sword-rack or -box seems intended, which was perhaps in the shape of a cross and gallows (a t-shape)” & gives a list of other proposed solutions, which include: shield, scabbard, gallows, sword-rack/gallows, cross, harp, ornamented swordbox (?), or tetraktys.2 Paul Baumm, in his 1963 translation, numbers this riddle among the “Chiefly Christian” category, offering “Scabbard” or “Cross” as its solution.3 The recent Dumbarton Oaks edition suggests “Wæpen-Hengen” [Weapon-Rack], which is no more convincing for being rendered in some form of Old English. The issue with most of these suggestions is that they’re close to being named outright in the riddle itself.4

Riddle 53 is a poem I never cared about & never imagined caring about. I translated it not out of honest interest but because completing the entire collection requires all of its contents be completed, like it or not. However, this is not a story of sullen drudgery, nor the resentment that can brew, but of new insights made possible by refusing to accept complacently the unexamined assumptions of past scholars. This is a brief account of what can happen during furious acts of (re)translating the all-too familiar text.

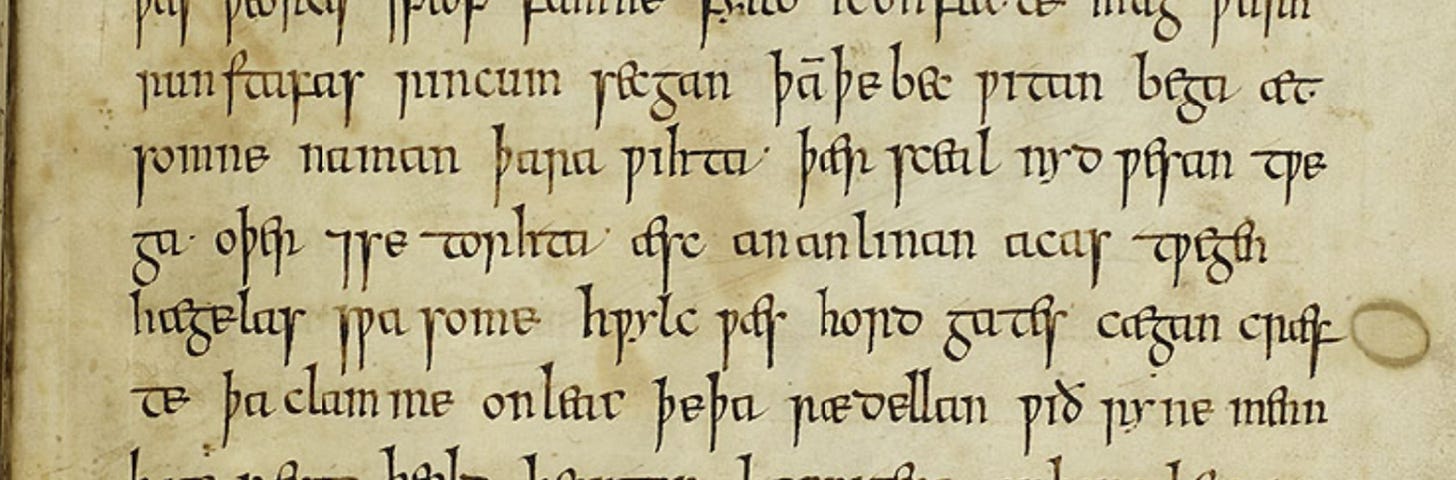

Here’s the Old English text:

Ic seah in heall, þǣr hæleð druncon,

on flet beran feower cynna —

wrǣtlīc wūdu-trēow ond wunden gold,

sinc searo-bunden, ond seolfres dǣl

ond rōde tācn, þæs ūs tō roderum up

hlǣdre rǣrde, ǣr hē hel-wāra

burg ābræce. Ic þæs beames mæg

ēaþe for eorlum æþelu secgan.

Þǣr wæs hlin ond ācc ond se hearda īw

ond se fealwa holen; frēan sindon ealle

nyt ætgædre, naman habbað ānne,

wulf hēafed trēo, þæt oft wǣpen abæd

his mon-dryhtne, māðm in healle,

gold-hilted sweord. Nū mē þisses gieddes

ondsware ȳwe, se hine on mēde

wordum secgan hū se wūdu hātte.5

And here is more or less literal translation by me, composed back around 2015:

I saw in the hall, where heroes were drinking,

borne onto the floor, four kinds

of wondrous wood and wound gold,

cleverly bound treasure and a portion of silver

and the token of the Cross, of him who

reared a ladder up to heaven, before he

broke open the city of the Hell-dwellers.I can easily speak of the lineage of that tree

before the earls—there was [hlin] and oak

and the hard yew and the fallow holly—

Together they are all useful to lords,

going by a singular name: wolfshead tree.One often receives this weapon from his lord,

treasure in the hall, a gold-hilted sword.

Now show me the answer to this song,

you who presumes to speak wordfully,

what this wood is called.

Those inclined to see a cross or the Cross must depend on line 5’s “ond rōde tācn” (and the sign of a cross), taking it for a direct confession. Yet there is an important generic quandary here: when dealing with riddles the most obvious solution cannot be the answer. This means if you’re certain of an answer, it’s likely you’ve stumbled into an interpretive snare & need to keep looking over the evidence. Riddles are duplicitous & ambiguous. That’s why the sexual riddles work so well: because those clues triggering a naughty image can just as easily be read as something less fraught. In fact those sexual riddles are usually interpreted this way — Do you see a penis? Nasty novice, it’s really an onion — So it’s a little odd that anything not obviously risqué but also seemingly uncomplicated might be taken at absolute face value.6

For example, Riddle 73 (ASPR #77) is unequivocally solved as “Oyster” despite the obviousness of that answer, a direct connection made possible mainly by a strategic emendation in the first two words & some reconstruction of manuscript damage. Yet seen only in light of this most obvious response, I am quite skeptical — there is no enigma to be found. Aristotle likened riddles to metaphors, saying: “Good riddles do, in general, provide us with satisfactory metaphors; for metaphors imply riddles, & therefore a good riddle can furnish a good metaphor” (Rhetoric, 1405b4-6), which suggests they also function by some separation between “vehicle” & “tenor”; between the words on the page & their immediate literal meaning compared with the implicit yet totally present figurative meaning lying beyond that statement. If we must insist upon these poems as a part of the Riddle genre (not that we have to), then we ought to avoid copping out at their most banal, literal level. Instead, I advocate for steering in the direction of their trope & speculate about what this lyric is really trying to do.

In the famous Riddle 45 (ASPR #47), there is no solution because there is no puzzle — at least if the poem is taken at face value. It begins “Moððe word fræt” [a moth devoured a word], as plainly as be, and so the game is over before it even began. Scholars might suggest the poem pondering some sort of natural paradox, but saying it’s weird that a bookworm eats books is hardly interesting. There are a few others in this category & none seem useful in the slightest interpreted so literally — certainly not worth the trouble & excuse of copying them into the manuscript.7

So, my friends, let’s start by assuming that Exeter Book Riddle 53 is in fact worth the effort of its inscription. Or arguing about at all, for that matter.

There are certainly many words & images that suggest a cross or some kind of wooden implement, most shared by the famous Vercelli Book poem, the Dream of the Rood: the confluence of “wūdu-trēow” [3, lit. woody tree], “beames” [7, of (the) wood/tree], & “wūdu” [16, wood/tree]. We hear that this wooden thing is “wrǣtlīc” (3, ornate), bound cleverly [searo-bunden, 4] in “wunden gold” (3, wound/twisted gold), “sinc” [4, treasure], and “seolfres dæl” [4, partly in silver/a portion of silver]. This elaboration corresponds with accounts of the True Cross from the Dream of the Rood or the hagiographic romance Elene (by Cynewulf). And the appearance of the well-known phrase “rōde tacn” [5, token/sign/symbol of the cross] pushes us even further towards the religious.

Yet a sign of the Cross is not the Cross itself, but even that semiotic truth doesn’t preclude any cruciform solution. Obviously, the reference is there, as indicated by the presence of a few catechistic points following (ll. 5b–7a). This may emphasize a few ideological necessities of the faith but perhaps has the paradoxical effect of distancing the poem from the immediacy of a theological statement. Those points of belief are essentially rote, as ideological responses usually are. World without end. However true or needful, they don’t point at a solution. They might just anticipate a response instead.

Wenzel commends the riddle’s structure for invoking some sort of devotional object but most likely intending to represent something more mundane as solution. In this way, Riddle 53 resembles the “sexual riddles” by advancing an image that is so ideologically charged it would be tough to think around it (some would argue there is an erotic charge to a cross though). In this way, EBR53 resembles the second part of 45/46 (47/48) or 56 (58), both of which strongly suggest other devotional objects (a chalice or rosary, respectively) but upon closer inspection have much more going on.

Two aspects of the riddle seem most elusive, and perhaps hold the key to its experience. They’re both found in lines 9–12. First is an apparent catalogue of trees or wood that corresponds to line 2’s “feower cynna” (usually understood as “four kinds [of wood]”). Second is the cryptic term, “wulf hēafed trēo” in line 12. They’re both confounding & powerful, because where a reader comes into the poem determines what they see these two moments as meaning.

I’ll start with the second part —

“Wulf hēafed trēo” appears just like that in the manuscript & happens to appear nowhere else in the extant corpus. It’s usually understood as a three-part compound word, something like “head of wolf tree.” It’s basically the rule in OE manuscripts that any compound word will be found with its parts separated by spaces. The only reason one can tell it’s probably a compound is that only the final verbal element will have a declensional ending.8 If the compound is structured schematically as “x-y,” the phrase can usually be interpreted as “y of x” and often some metaphorical relationship can be deduced. For example: “hran-rād” (BW l. 6 et al.) = “road of whales” = “ocean.” Not all of these compounds work identically or have to be figurative expressions, but the general idea holds for EBR53.9

“Wulf-hēafed trēo” seems to combine a metaphorical kenning [wulf + heafed], which then becomes a descriptive term limiting “tree,” much like “oak tree” [āc-trēo]. So “wolf-head tree.” But what is a “wolf-head”? Most critics look at the later legal formation from English Common Law to designate a state of outlawry. The OED’s earliest citation is uulfesheued, glossing in English the Latin “Lupinum… caput” (in the Laws of Edward the Confessor, ca. 1000 CE). The OED also cites the phrase “to cry wolf’s-head,” meaning to call for someone to be treated as an outlaw, though not attested before the 14th century. There is nothing else resembling the full compound in OE, except in EBR53. A close match is found in “wulfes heafod-bān” (“bone from a wolf’s head, perhaps) found in the OE Leechbook, but this is probably non-figurative, an actual wolf’s bone & not some kind of plant.

It’s quite possible such a legal term was in circulation in early English — and a feasible definition of the compound as it appears in EBR53 is “gallows”: a tree upon which “wolf’s heads” (or outlaws) can be found. Because of this, any solution of “gallows” is automatically suspect. The cross can be compared to a gallows as well, but that’s also tantamount to stating that solution outright.

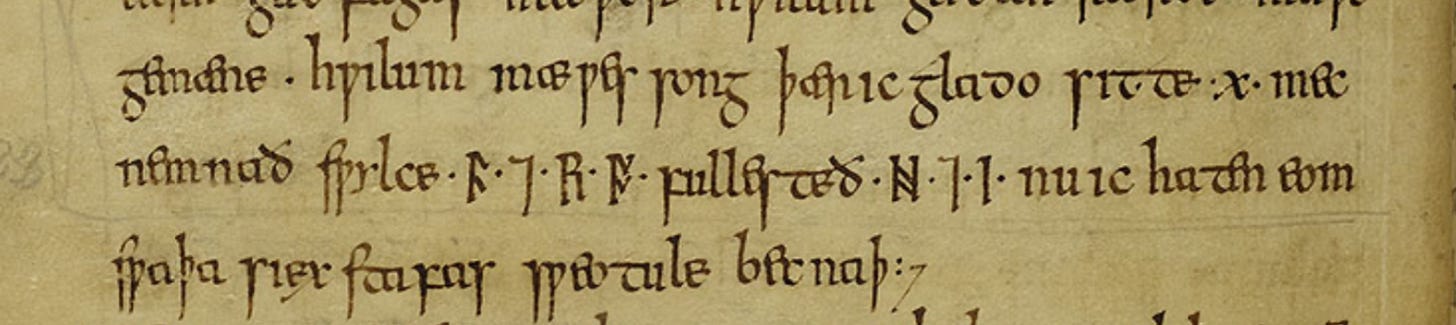

The real puzzle comes in this putative catalogue of wood found at lines 9–10: “Þǣr wæs hlin ond ācc ond se hearda īw / ond se fealwa holen” [There was hlin & oak & the hard/severe yew & the yellow/dusky holly]. Hlin is somewhat obscure — it’s often interpreted as “maple,” by comparison to the Old Norse hlynnr. The Dictionary of Old English states this connection is “doubtful,” preferring to connect the term to ‘lime-tree’ [not the citrus] or ‘linden.’ There’s supposedly a bit of apocrypha involving the Cross as made of the wood of the maple, oak, yew, & holly trees — but that’s no reason to prefer hlin as ‘maple’ if not linguistically sound.10

I’m interested in approaching this moment as enigma rather than apocrypha. That is, as another sort of puzzle:

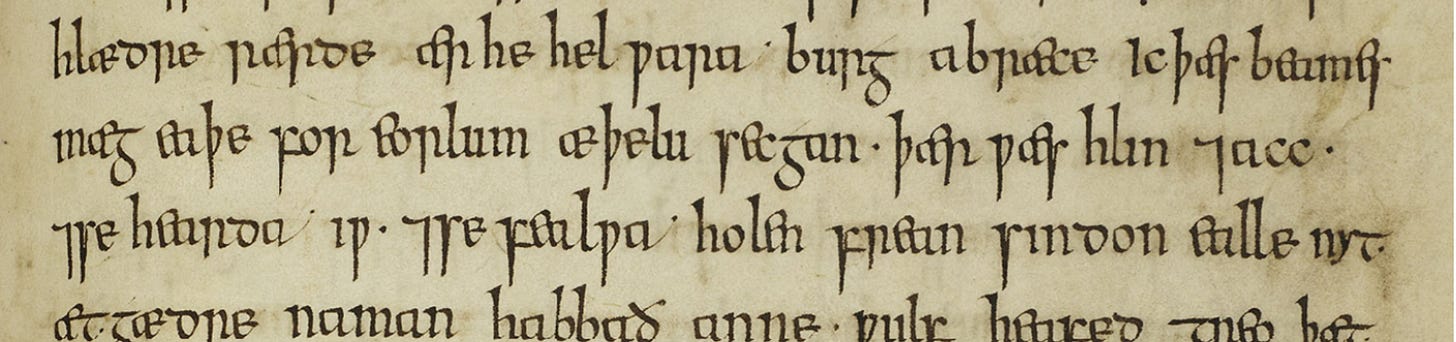

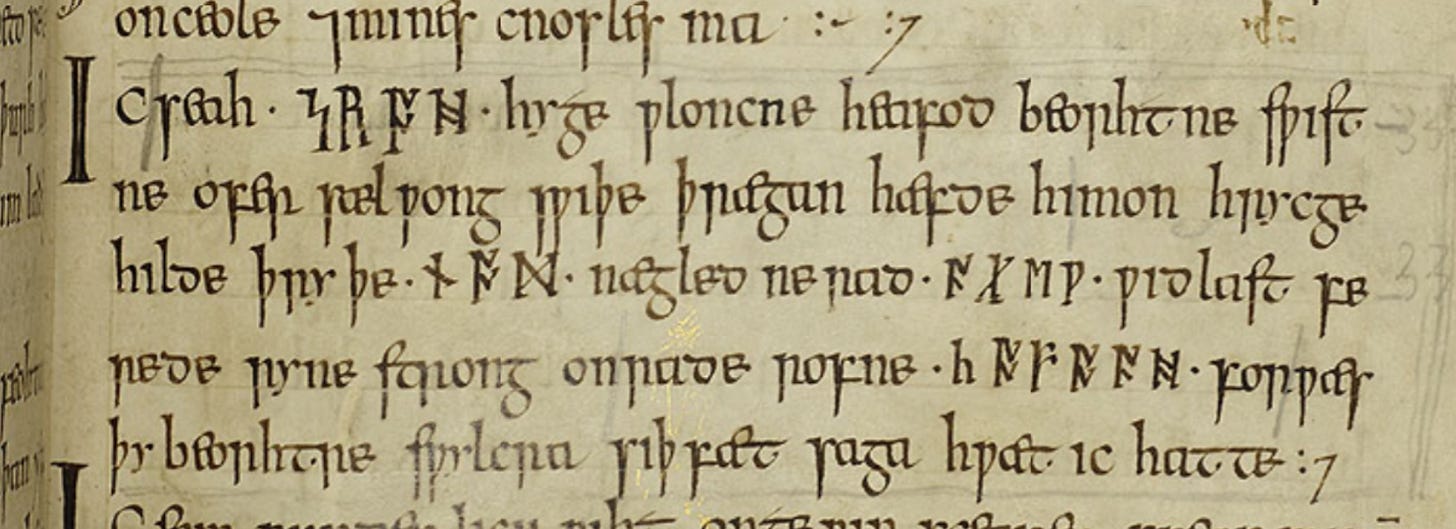

As shown above, both the words acc & iw have a raised punctum after. These ‘points’ are a sort of punctuation mark common in OE manuscripts, though it’s still not entirely certain what they mean in every case. One use is fairly predictable: puncta usually surround Roman numerals or runic characters to specify them as numbers or runes (as seen in the examples below). And Āc[c] & īw happen to be the names of runes: āc (oak) = |a| & īw (yew) = |i:| or |x| or |ç|.11

There are other runic puzzles among the riddles: in EBR17 (below), strings of runes spell out words like “HAOFOC” and “MON,” though from right to left. In EBR22 (also below), the runes appear as if in a sentence, but may form an anagram of the solution. I discuss this riddle in more detail here.

In other runic puzzles among the riddles, a rune’s name appears spelled out, rather than using the futhark character, such as in EBR40/41 (42/43) or 56 (58). In 40/41, these names are given as a spelling game, which may or not be the “solution.” But in this case, the rune names are not surrounded by puncta & possess declensional endings.

But maybe the puzzle here is a bit more intricate. I see these lines & recall the cryptic crossword genre, popular in the UK & found in the Times Literary Supplement. Each clue is broken into two parts: one half is the definition of the answer & the second part is the instructions for coming to that answer. The challenge to the puzzle is figuring out where one part ends and the other begins. In puzzles of this sort, it’s vital to pay attention to subtle differences of spelling & syntax, to notice if anything seems conspicuously odd. With that in mind, then let’s examine the language here for clues, followed by a looser, more speculative translation:

Þǣr wæs hlin ond ācc ond se hearda īw

ond se fealwa holen; frēan sindon ealle

nyt ætgædre, naman habbað ānne…There was HLIN and ([ĀC] + C) and that hard [ĪW]

and that [dusky] HOLEN. All of them together

are useful to Presiding Purpose, [yet] they have only one name.

Here we see four words that are said make up something useful yet have only one name. One of these words is of uncertain meaning (hlin), two (ac & iw) are, as I pointed out above, also the names of runes (so possibly single letters), the first of these has a somewhat unusual spelling (adding an extra -c), two are accompanied by a demonstrative pronoun & an additional adjective (se hearda īw & se fealwa holen). And finally, the last word in the series of four can be read in two different ways: as holen, m. = “holly[-tree]” or as the past participle of the Class IV strong verb helan = “to conceal, hide.” Taken as a substantive adjective, this could be understood as “this thing that has been concealed” = “problem/puzzle/riddle.”

“Fealwa” is an interesting word. The direct ancestor of “fallow,” as in “leaving a field fallow,” it can be seen in two forms in OE. As an adjective, it can refer to a yellowish brown color but also something dusky or dark. The word can be seen in The Wanderer, ll. 45–6: “Ðonne onwæcneð eft wineleas guma, / gesihð him biforan fealwe wegas” [Then the friendless man wakes all too soon, / seeing before him the dusky waves/the fallowness of waves]. The color of the ocean can be tough to pin down sometimes.

As a noun, it can also be used to refer to arable land deliberately left untilled, usually to restore nutrients to the soil for better crops next season. This is an agricultural practice that began in the early Middle Ages in Europe, because wheat cultivation tends to deplete the soil of nitrogen from year to year. The two words seem to have evolved together, though they may have come from different Proto-Germanic stems: fallow (n) → OE fealg → PGmC *falgu vs. fallow (adj) → OE fealu → PGmC *falwaz. So what we see in EBR53 may be another possible pun based in two homonyms. Holly wood may be dusky in color, but a “fallow puzzle” might be one currently inscrutable but ready to bear fruit in the future.

Now, if we take all the pieces that may refer to letters, we get: H L I N + [A] + C + [whatever sound īw represents]. Āc (ᚪ)is pretty straightforward; it seems safe to assume it is |a|. However, this where that adjective modifying “yew” may be very useful. A “hard ᛇ” may give us a bit of direction here: the difference between the voiced |x| and the unvoiced |ɣ| may well be perceived as “hard” vs. “soft.” Both are sounds that came to be represented by “yogh” ( ʒ ) in Middle English, and often descend to PDE in words that end in “-ow” (like borough [burh], plow [plōh]), or yellow [geolh]) or in the “-ght” (like daughter [dohtor], ought [ahte], right [rihte]).

I am suggesting that some anticipated response to EBR53 may be arranged as an anagram of these letters, otherwise why through the trouble of giving such an strange statement (even for a Riddle). Yet what that word might be is tough to ascertain. F. Liebermann, in a brief scholarly note in 1905, suggested that the phrase yields the letters “IALH,” claiming it was another spelling for gealga or “gallows.” The suggestion is intriguing — but as Wenzel offers, the connection & the spelling are a bit strained.12 Many of these early arguments require the Riddles to have extremely early dates, like pre-written literacy dates (before ca. 700), and therefore would yield solutions that would have little provenance three or four hundred years later, when the Exeter Book was compiled.

I realize that this may feel like a cop-out, but I really don’t know right now what this “cryptic crossword puzzle” clue might yield. Part of the reason is that the voiced |x| and the unvoiced |ɣ| velar fricatives could be spelled in numerous ways. Also, it’s difficult to play anagrams in a language I am not a native speaker of, where spelling was not yet standardized and, mosty importantly, we have only a fraction of the words available to an educated reader in late-tenth century England, in any of that region’s dialects or languages in likely use (English, Latin, Scandinavian, & Celtic). I also don’t like the presumption that there may only be a single, “official” answer to these odd little birds that seem to determined to thwart our every move.

So, no — I don’t know what the solution of Exeter Book Riddle 53 would be.

Must I do your job as well?

The Exeter Book Riddles either considered “unsolvable” or still without general consensus about a solution include (ASPR #s in parentheses after): 2 (4), 26 (28), 37 (39), 39 (41), 62 (64), 67 (67/68), 71 (74), 75 (79/80), 90 (95). I’m not counting Riddles that are too incomplete to determine, which make up another ten in the collection.

Bernard J. Muir, ed., The Exeter Anthology of Old English Poetry: an edition of Exeter Dean & Chapter MS 3501, 2 vol. (University of Exeter Press, 1994), II, 622.

Paul F. Baumm, The Anglo-Saxon Riddles of the Exeter Book (Duke UP, 1963), 17. Baumm renumbers the Riddles according to his own scheme, by category of solution. My EBR53 is given the number #13 in his volume.

Franziska Wenzel, in her commentary on this riddle found on the Riddle Ages website, surveys the case for these various solutions, wisely locating their shortcomings before moving on to the next. I admire her lack of hurry to resolve the problem, but “to enjoy it for all its beauty.”

As always, my text of the Exeter Book Riddles is based on Muir’s edition though carefully compared with the digital facsimile of the Exeter Book manuscript, as well the Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records edition (Krapp & Dobbie, 1936) & Craig Williamson’s 1977 edition of the riddles. The majority of textual emendations are ignored if a legible reading can be discerned without, often with quite dramatic results.

The so-called “sexual” riddles (better than the previous “obscene” riddles, but still an unsatisfying designation) are numbered at around eighteen & usually include: 10 (12), 18 (20), 19 (21), 23 (25), 35 (37), 40 (42), 42 (44), 43 (45), 44 (46), 52 (54), 59 (61), 60 (62), 82 (87), 86 (91). Very much the aforementioned “Nasty Novice,” I consider another fourteen riddles potentially belonging, but with the caveat that the entire idea of the category presumes that 1) early English readers would have had the exact same ideas of decency & indecency as sex-bashful Victorian-era bachelor-professors, and 2) poems about desire, genitals, sexuality, gender, rape, &/or excretory functions are all somehow inherently spicy or prurient and therefore forbidden to speak upon.

Exeter Book Riddles that seem to fall into this category include: 1 (1–3), 11 (13), 13 (15), 17 (19), 18 (20), 21 (23), 22 (24), 40/41 (42/43), 44 (46), 45/46 (47/48), 53 (55), 57 (59), 62 (64), 68 (71), 72 (75/76), 73 (77). Several of these are thought to encode a solution in Germanic runes or other kinds of graphic gaming. Some dwell on natural phenomena, like a storm or an animal. This list doesn’t include several that are deemed faithful enough translations of Latin riddles to have the same solution, such as 33 (35), 38 (40), 64 (66), 80 (85), 81 (86), 89 (94).

An interesting example of this appears in EBR 18, where two compounds are given as kindred though contrasting terms. Line 27’s “bearn-gestrēona” is paired against line 31’s “hæleþa gestrēona,” related through parallel construction (both are genitive plural objects of þolian & brūcan (to do without vs. to enjoy having), with their first element indicating the thing either missing or enjoyed. But the second one conjugates the first term (hæleþa [men]), as if to call attention to that moment, that it might be alarming or unexpected.

Remember that compounding is the preferred form of word formation in many Germanic languages. An “acorn” is formed of āc + corn, or “seed of oak” & a “woman” is wif + mann, or “woman-human.” These compounds may have started as figurative expressions, but have since lost their metaphoric nature.

The only source I could find for this biut of lore is Baumm’s notes on his Riddle #13 (The Anglo-Saxon Riddles of the Exeter Book, 17).

The Old English Rune Poem has a stanza for yr (ᚣ = |y|) & gear (ᛄ = |j|), as well as īw (ᛇ = ?). There are also runes for eoh (ᛖ = |eə|, the “eo” diphthong), eþel (ᛟ = |e|), iar (ᛡ = ia), ēar (ᛠ = |æə| the “ea” diphthong) — which means that an awful lot of similar vowel sounds were converging around this time & making it less clear what sound īw would stand for. It is possible that this rune functions like ing (= |ŋ|) instead, used for a sound that never appears in an initial position. Michael Barnes suggests ᛇ may have been used for |x| or |ɣ|, velar fricatives often spelled “h” towards the end of words or syllables (e.g. ploh, niht, leoht, wealh, etc.).

Franziska Wenzel, Riddle Ages. F. Liebermann, “Das anglesächsische Rätsel 56: ‘Galgen als Waffenständer’,” Archiv 114 (1905), pp. 163-4.