Translating from the Trenches, vol. 2

Walter Benjamin & Avoiding the “Same Old Same Old”

This here’s the second installment of “Translating in the Trenches,” a semi-regular feature, wherein I attempt to unravel popular misgivings about translation as offered by angry or defensive commenters on my other blog site, The Old English Poetry Project. Rather than ridicule or snark at these comments, my plan is to offer an explanation of the translation theories that motivate & justify my choices & program. The first part can be found here. Part Two begins beneath the “Subscribe” button.

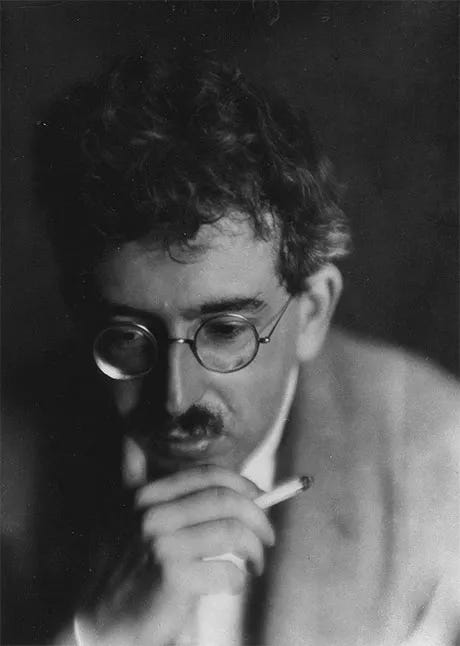

In the previous installment of “Translating from the Trenches,” I responded to two charges by one angry troll, two grievous no-no’s in this person’s eyes. Last time I addressed their accusation that my lexical choices amounted to disrespect to The Seafarer, a notable Old English lyric (notably translated by notable American fash poet Ezra Pound) and to the canon of English literature it represents. My second fault in their eyes was that one particular choice of words could not be true to the meaning “intended” in the source poem. The two charges are related, though I addressed the first by explaining Lawrence Venuti’s idea of “heterogeneity” as a deliberate strategy of seeing a text in a new light. In this one, I’ll look at Walter Benjamin’s understanding of translation — particularly as he explains the language of a translation.

Once again, here is my troll-like friend’s comment:

In today’s installment, let’s discuss this one’s objection to “hours of fuckery” used for “earfoð-hwīle” [a period of hardship, basically] in The Seafarer, line 3a. Although the case really boils down to no more than “you translate your way, I’ll translate mine,” there is still a theoretical point to be made here.

In crafting a theorized (re)translation of this canonical poem, I deliberately set sail with the intention of rattling cages & unsettling the complacent, to mobilize “heterogeneity” in order to uncover new ideas about its interpretation, aspects & possibilities previously unseen there. But I also knew it would cause trouble as well: The Seafarer is one of the three shorter Old English poems (beyond Beowulf) most taught, most studied, & most admired — especially by those outside the academy.1 Most folks’ most cherished ideas about the era & its literature are derived from these three texts (representing a grand total of 395 lines of the entire corpus). So please don’t think I was ever surprised that some would get incensed with my choices.

On this project of (re)translation, I found lots to work with among Walter Benjamin’s concepts of translation as expressed in his much-misunderstood essay “Die Aufgabe des Übersetzers” (1923, “The Translator’s Task”).2 Here, the philosopher challenges us to reconsider what we believe we know about the art of translation, deforming terms we assume we understand & defamiliarizing its dynamics of language, time, canonicity, and interpretation. Carol Jacobs argues that the essay itself “translates” the idea of translation: it “dislocates definitions rather than establishing them”; working to unsettle its every complacency.3 And complacency is what gives most readers such unearned confidence about what a translation is, or should be, and work it accomplishes. But a translation is really a funhouse, where all perceptions become warped as one goes.

Most assume it’s simply a matter of finding an equivalence in language between two words — what any computer algorithm can accomplish. However, no word in any language is exactly the same in the sum of its meanings as any other — even if that word is borrowed from that other language. Benjamin might say that even though these words have similar intentions, their differences keep them from signifying the absolute same thing.

While this may seem like a hopeless quandary, it’s actually one of the most glorious aspects of language. I will need a whole post of its own to discuss Benjamin’s article & how it influences my project, so let me zoom in on just one aspect: wherein the task of the translator lies. He argues that a poetic translation must move beyond merely replicating the plainest sense of the source text’s words, which would only produce what he terms its “Dasselbe” [“the same old same old,” perhaps]. Those sorts of translation pretend that, at some level, there is no difficulty in transferring a word or idea from one language and/or time to our own, deluding themselves (& their readers) into accepting as legitimate what Walter Benjamin might call a “hallmark of bad translations” (Erkennungszeichen der schlechten Übersetzungen).4 Such products render only the source text’s “information” rather than respecting & celebrating the real spirit of any text, which inheres in all the markers of meaning constellating around those words.

In this manner, a translator performs a sort of impossible alchemy upon their source text: to take the unified essence of the original, its inseparable connection of form, language, and content, and then to invent a poetic language powerful enough to express that non-reproducible quiddity. The effort requires the invention of a new vernacular that defamiliarizes both the source & target language. As Benjamin states:

One can extract from a translation as much communicable information as one wishes, and this much can be translated; but the element toward which the genuine translator’s efforts are directed remains out of reach. It is not translatable, like the literary language of the original, because the relation between content and language and the original is entirely different from that in the translation. If in the original, content and language constitute a certain unity, like that between a fruit and its skin, the language of a translation surrounds its content, as if with the broad folds of a royal mantle. For translation indicates a higher language than its own, and thereby remains inadequate, violent, and alien [unangemessen, gewaltig, und fremd] with respect to its content.5

We may find acceptable approximations for ideas & words, but that is not the most essential aspect of translation. What is most vital to the experience of the source text, what Benjamin calls its “Kern” [seed], is an inseparable mélange of form, content, & language, bound together as “Fruche und Schale,” as a fruit to its rind. This unity of significance starts at each individual word & extends to the whole text itself. Two words in two languages may denote the same thing, but their connotations (what they suggest or imply based on common contexts) will differ, their sonic relations to other words in that context (e.g. alliteration, assonance, consonance, various forms of rhyme), other kinds of sound-likeness (such as puns, homophones, slang usage, et al.) may be different, their etymological genome may vary, & the history of their uses & associations might be worlds apart. Similar degrees of difference pull texts or poetics or genres apart as well — French octosyllabic romance does not feel or sound the same as Middle English octosyllabic romance; an Italian sonnet by Petrarch does not come off the same as a Petrarchan sonnet by Sir Thomas Wyatt. Jorge Luis Borges was not just fooling around when he wrote about Pierre Menard’s attempt to rewrite Don Quixote: just by transposing the writer, the era, the effort — everything changes.

To translate the untranslatable requires a new sort of language, something that does not quite feel like either the source text or the target language, that endeavors to communicate the spirit, the feeling, the vibe of that source text without fully domesticating that foreign voice or pretending to supplant the experience of the original. A way of speaking that might enrich or ennoble the original, wrapping it up like the glorious amplitude of a king’s cloak [ein Königsmantel in weiten Falten] — not changing it necessarily, but casting the source in a new light. The shift in metaphor here is purposeful & significant: a fruit is intimately connected to its skin: they are made to be together—they may be peeled, of course, but neither are ever the same again afterwards. However, the regally-garbed translation is dazzling & fascinating, yet is also a screen over the source — it lets you know something worthy is there, but also stands across that direct experience, the tabernacle over the Ark of the Covenant.

This “higher language” [höhere Sprach] the task requires is also the site of turbulent contradiction. The sense of the phrase is likely to be “transcendent,” rather than conveyed in a more formal register, dialing up the pitch to match the Messianic implications of Benjamin’s argument. Yet this transcendent language nevertheless can only be “inadequate, violent, and alien” to the experience of the source text, three most titillating adjectives for the task. Unangemessen signifies “inappropriate” or “inadequate,” that the translator will never find a lasting correspondence between the source & target. Gewaltig can mean “violent” as in “tempestuous”: that the translation must wrench the source’s words into its own control. And fremd describes this language as “alien” to the original, that it must “estrange” the experience of that text.

According to Benjamin, even the “best” translations can never be more than imperfect and contingent — they are fated to pass away in time to a new generation of translators & translations. Yet these “best” translations make themselves comfortable in this temporary relation. They exult in their own voice, glorying in the ability to render WHY one must experience that source text. Benjamin cites Rudolf Pannwitz’s characterization of the mistake most literary translators make: “… the fundamental error of the translator is that he holds fast to the state in which his own language happens to be rather than allowing it to be put powerfully in movement (gewaltig bewegen) by the foreign language.”6

OK, so let’s return to the comment, for how what I’ve just explained addresses their concerns. Just for fun, I’ll lay it out as a running response, sort of like a medieval exegetical commentary:

So, I think this is a truly terrible translation…

Ok, cool — thanks for stopping by. One can’t please everybody.

… because in trying to sort of Gen Z-ify the language, the translation entirely misses most of what is essential about the poem.

So you say.

For instance, “earfoðhwile” refers to genuine, often terrifying hardships and risks like treacherous weather, piracy, shipwreck, etc.

I said as much in my reply to the original comment, but I think we can be reasonably sure that if the Seafarer were meant to be some photo-realistic account of being at sea, some of these things would be directly addressed. Instead, we only hear the speaker is cold and lonely, that they are tossed by waves & regaled by seabirds, but that this loneliness is preferable to any sort of life on land. Given the energy & imagery of the poem, along with its lack of specifics of ship-bound life, it is far more likely that the poem is meant as an allegory for the monastic, contemplative life. To say it differently, the speaker knows about as much about life at sea as I do. Or you for that matter, outside watching some TV show on Vikings.

These are not covered by the phrase “hours of fuckery,” which makes it sound like he’s been on a lengthy hold with his cable provider.

Although friend, you think this is some kind of a burn, as I indicated above, this speaker endures boredom, loneliness, and cold — all things any contemporary person might term “fuckery” — as in some unpleasant drudgery one is compelled to exist through.

Also, my rendering of “earfoð-hwīle” is designed to unsettle the received scholarly opinion of what this compound word or kenning conveys. It is fully possible to translate & interpret these literally, but it’s also useful to think around the various possible means of its component parts. Hwīl seems fairly clear, as it most often means “some unspecified span of time” (DOE, “hwīl,” n.). And the first element, “earfoð,” while usually rendered as “tribulation” or “suffering,” can mean just “trouble,” hardship,” “labour,” or even “inconvenience” (DOE, “earfoþ,” n.).7 So what I see here isn’t actually all that off from the dictionary senses, even though traditionally OE scholars have always understood the word in a large-scale, apocalyptic, or martyr-like way.

Also, there is almost always some figurative intention in their appearance. In this case, “earfoð-hwīle” is a compound unique to the Seafarer (as are many others), and so some effort ought to be taken to ponder “why here?” The literal level is always present for any instance of figurative language, but there is also a generative tension between the drag of the literal & the pull of the metaphorical. Unfortunately, there’s a long-standing tradition in the academy to interpret any work of OE literature not immediately identified as religious (& therefore allegorical) as literal, only what’s given on its surface. In this view, the speaker of the Seafarer MUST BE a sailor because they discuss sailing.8 What then is that metaphorical dimension? Maybe that “earfoð-hwīle” is the term of human existence, that all of us live in a “space of trouble” while in this life? Maybe it’s the contemplative life, something that by definition is not fraught with “weather, shipwreck, & piracy”? It’s tough to say — and though I interpret the poem through my translation, mine is not the only interpretation possible and there’s no real way to say what the “correct” one would be. We can deal in probabilities only, not absolutes (sorry, sport)…

But let’s move on—

The same issue plagues virtually all the places in the translation where deep emotion and crucial social relationships are reduced to trendy youth-speak (“Those dudes” completely misses the kind of loyalty, love, dependence and transaction that formed the critical and deeply respectful relationship between a warrior and his lord).

I hardly know where to start here. Perhaps I’ll give the passage from which the offending informality was taken:

Those days go dusking: pomposities of every earthly prince — no more the kinglets or kaisers, no more the gold-givers, like there used to be. My my — then those dudes would grant out the greatest glories and home them in highest honor. Dagas sind gewitene, ealle onmedlan eorþan rīces; nǣron nū cyningas ne cāseras ne gold-giefan swylce īu wǣron, þonne hī mǣst mid him mǣrþa gefremedon ond on dryhtlīcestum dōme lifdon (SF, 80b–85)

I’m not sure how much more brown-nosing this one would prefer me to be. The moment is part of a lament on how there is nothing left of value for a land-bound life, that the glories of the heroic world have passed away for good, so that, even if cold & boring, this “ship existence” of the contemplative life would be preferable. This is not, however, a nostalgic passage: the very idea of holding to these long-gone ways of life is contemptible, useless. The speaker states that the only reward the warrior life could ever promise was “Forþon þæt bið eorla gehwam æfter-cweþendra / lof lifgendra last-worda betst” [72–3, Therefore the best for every noble will only be the regards of those rambling after].

So I think the better question here is: why are you choosing to ignore all this context to support a tepid & passé reading made famous by Pound’s beautifully-worded but much-bowdlerized translation. Also, & not for nothing, the entire poem of Beowulf is choked by the shadows & spectres of the fratricide, treachery, & internecine violence (no small share of which is suspected of our hero himself) that actually “formed the critical and deeply respectful relationship between a warrior and his lord.” So there.

I guess all that remains is for me to address this one’s closing statement:

At the points where the translation doesn’t miss what’s essential, the effect is dissonant with the casual references to “Chads,” “frenemy,” etc. The reader comes away from this with no sense of The Seafarer’s impact or language.

Given that this commenter does not appear any clear idea of the Seafarer’s “impact or language,” or whatever is “essential,” I can only conclude that their main objection is that my (re)translation’s more contemporary language & less formal register offends the imaginary spirit of early English culture that they built up for themselves in their head. To this view, anything that doesn’t assert that culture to be decorous, pious, loyal, honest, & virtuous is betraying the whole “Anglo-Saxon race.” But I need to be clear on this, Mary — I am no “Anglo-Saxon” & neither are you, even if you’re a white person from England. There is not now nor ever was such a thing. So I think it’s time we gave up on the false piety & fatuous myth-making about that culture. There are still many crucial things to learn about the period, but that will be tougher if we still buy into these nursery ideas.

Otherwise, I leave the rest of my readers with one last notion from Walter Benjamin, a lovely thought on the contingency of a translation, on how any translation relates to its source text.

Translations, on the contrary, prove to be untranslatable not because the sense weighs on them heavily, but rather because it attaches to them all too fleetingly.

[Übersetzungen dagegen erweisen sich unübersetzbar nicht wegen der Schwere, sondern wegen der allzu großen Flüchtigkeit, mit welcher der Sinn an ihnen haftet.]9

Stay tuned for future installments of “Translating from the Trenches”: I got plenty of hate-mail, so there’s never any shortage of material. Tchuẞ!

The other two shorter poems are The Wanderer (also in the Exeter Book) & The Dream of the Rood (in the Vercelli Book). Both of these manuscripts are compiled between 950–1000 CE. Although fragments of two lines of the latter poem are found carved in runes on the Ruthwell Cross, probably in the 8th c., there’s no reason to believe the entire poem was composed, in the same form we have it, that early. The other major Old English poem is of course Beowulf (compiled 1000–1025 CE), but as a very long poem (3,182 lines), layfolk don’t often get agitated about granular-level readings. But also, the primary translation of Beowulf on my site is only a first run & not designed to make many waves. See my earlier post about a recent BW translation here.

This essay first appeared as the preface to Benjamin’s own translation’s of Charles Baudelaire’s “Tableaux parisiens” (“Parisian Scenes,” a section of Les Fleurs de mal [1857–67]). Most English readers may be more familiar with Harry Zohn’s translation, “The Task of the Translator,” as collected in Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt (Schocken Books, 1968). I use the translation by Stephen Rendall, presented in The Translation Studies Reader, 3rd ed, edited by Lawrence Venuti (Routledge, 2012). For the German text of “Die Aufgabe des Übersetzers,” I use the reprint found in Gesammelte Schriften IV (1972): 9–21.

Carol Jacobs, In the Language of Walter Benjamin (The Johns Hopkins Press, 1999), 76.

Benjamin, “The Translator’s Task,” 89 [“Die Aufgabe des Übersetzers,” 10]

Benjamin, “The Translator’s Task,” 93 [“Die Aufgabe des Übersetzers,” 15] (emphases mine).

Benjamin, “The Translator’s Task,” 96 [“Die Aufgabe des Übersetzers,” 21], citing Rudolf Pannwitz, Die Krisis der europäischen Kultur (1917), 240.

This final definition seems to be rare, but is found in Genesis B, line 513b–516a: “Nele þa earfeðu / sylfa habban þæt he on þysne sið fare, / gumena drihten, ac he his gingran sent / to þinre spræce” [He wouldn’t take such inconvenience upon himself, the Lord of Men,

to take this errand, yet he sent his subordinate to speak with you] (text of Genesis B from The Junius Manuscript, ASPR, vol. 1 (ed. Krapp & Dobbie, 1931). Translation is mine.

As usual, the great Roberta Frank comes with the goods: “Yet the Anglo-Saxon author's illusion of historical truth is so strong that it has been taken for the reality. We confuse the reconstructed fourth- to sixth-century world of Beowulf and the scop poems with the far different world in which their authors lived and worked, as in the following model of misrepresentation:

The subject-matter of the surviving poetry reinforces the picture of the position of the minstrel and the function of poetry which we have already gathered from glimpses of scops in action in the poems: that it was composed for recitation at court for an audience such as that depicted in Beowulf, the king and queen, their thanes and counsellors. (M. W. Grose & Deirdre McKenna, Old English Literature (Totowa, NJ, 1973), p. 48)

This is like saying that Walt Disney's animated cartoons were made for an audience of mice and ducks” (Frank, “In Search of the OE Oral Poet,” in Textual and Material Culture in Anglo-Saxon England: Thomas Northcote Toller and the Toller Memorial Lectures, edited by Donald Scragg, 137–160 [Woodbridge, UK: D. S. Brewer, 2003], 152–3. That’s Ru Paul’s Drag Race-level shade right there.

Benjamin, “The Translator’s Task,” 97 [“Die Aufgabe des Übersetzers,” 20].